The power of habit

Most of the choices we make each day may feel may appear to be the result of careful consideration but a Duke University researcher discovered in 2006 that more than 40% of the actions people took each day were habits rather than actual decisions. Individually, each habit may seem insignificant, yet it has enormous impacts on our health, productivity, financial security and happiness. Habits can be changed, break into parts and rebuild to our specifications. There’s nothing you can’t achieve if you developed the right habits.

“Individuals have habits; groups have routines,”

“Routines are the organizational analogue of habits.”

How habit formed

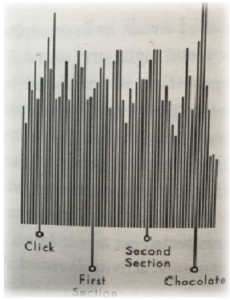

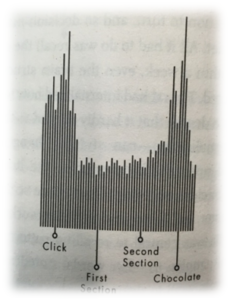

In the early 1990s, the MIT researchers began working on if the basal ganglia might be involved in habit formation. They conducted experiments on rats, inserting tiny wires to observe their brain activities. Rat was placed behind a partition after a loud click signalled them to enter a T-maze with a chocolate bar (reward). As each rat learned how to navigate the maze through dozens of routines, its mental activity dropped (Fig.1) compared to the first few times when brain power was at its peak (Fig.2).

The brain probes revealed that the basal ganglia were involved in internalization. The basal ganglia were crucial for recalling and acting on patterns. To put it another way, habits were formed even when the rest of the brain was sleeping.

The skull of a rat as it enters the maze for the first time. The brain is always attempting to make sense of all of the incoming information.

After a week, once the route is familiar and the scurrying has become a habit. The rat’s brain settles down as it run through the maze.

Chunking – roots of habits forming

This process, in which the brain turns a series of acts into an automatic pattern, is referred to as “chunking,” and it’s the root of habits formation. An efficient brain allows us to stop thinking constantly about basic behaviors, like walking and choosing what to eat, so we can dedicate mental energy to inventing spears, irrigation systems, and eventually, airplanes and video games.

This effort-saving instinct is a huge advantage. Our basal ganglia have created an ingenious method for determining when to allow habits to take over. The graphs in Fig.2 illustrate that those spikes are the brain’s way of deciding when to yield control and which habit to use.

For instance, it’s difficult for a rat to distinguish if it’s in a familiar maze or an unfamiliar cupboard. To deal with this uncertainty, the brain expends significant effort at the start of a habit looking for something—a cue—that provides an indication as to which pattern to adopt. And at the end of the action, when the reward appears, the brain shakes itself awake to ensure that everything went as expected.

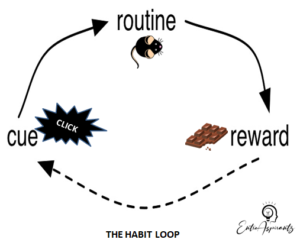

Habit loop

This process within our brains is a three-step habit loop. First, there is a cue, a trigger that tells your brain to enter automatic mode and which habit to employ. Then there’s routine, which might be physical, mental, or emotional. Finally, there is a reward, which aids your brain in determining whether this particular loop is worth remembering in the future.

This loop—cue, routine, reward—becomes increasingly more automatic over time. A habit is formed over time by combining a trigger cue, a routine, and a reward, followed by cultivating a craving that drives the loop.

When a habit forms, the brain ceases to participate fully in decision making. It causes you to cease working as hard or diverts your attention to order duties. So, unless you actively resist a habit—unless you develop new routines—the pattern will emerge on its own.

The problem is that your brain cannot tell between good and bad habits, and so if you have a bad one, it will constantly be lurking, waiting for the right cues and rewards.

The golden rule of habit change

However, you can never completely eradicated bad habits. Instead, keep the old cue and offers the old reward, but introduce a new routine. That’s the rule: if you apply the same cue, and provide the same reward, you can shift the routine. If the cue and reward remain the same, almost any behavior can be changed.

The Golden Rule has influenced treatments for alcoholism, obesity, and obsessive-compulsive disorders among other destructive behaviour. Attempts to stop snacking, for example, are generally futile until a new habit is established to satisfy old cues and reward urges.

How it works:

Use the same cue.

Provide the same reward.

Change the routine.

A reworked habit loop to a permanent behavior

Belief that change is feasible was the component that turned a reworked habit loop into a permanent behavior. Keystone habits are habits that cause a ripple effect – in which one small positive change has the potential to trigger other positive changes in all different aspects of someone’s routine.

Keystone habits initiate a process that, over time, transforms everything. Success does not rely on getting everything perfect at once, but rather on recognizing a few core priorities and transforming them into powerful levers. However, in order to modify a habit, you must first decide to change it. You must consciously embrace the effort of recognizing and replacing the cues and rewards with alternatives that drive the habits’ routines.

You must know you have control and be self-conscious enough to use it.